How Smoke and Heat Move Through an Offset Smoker

Introduction

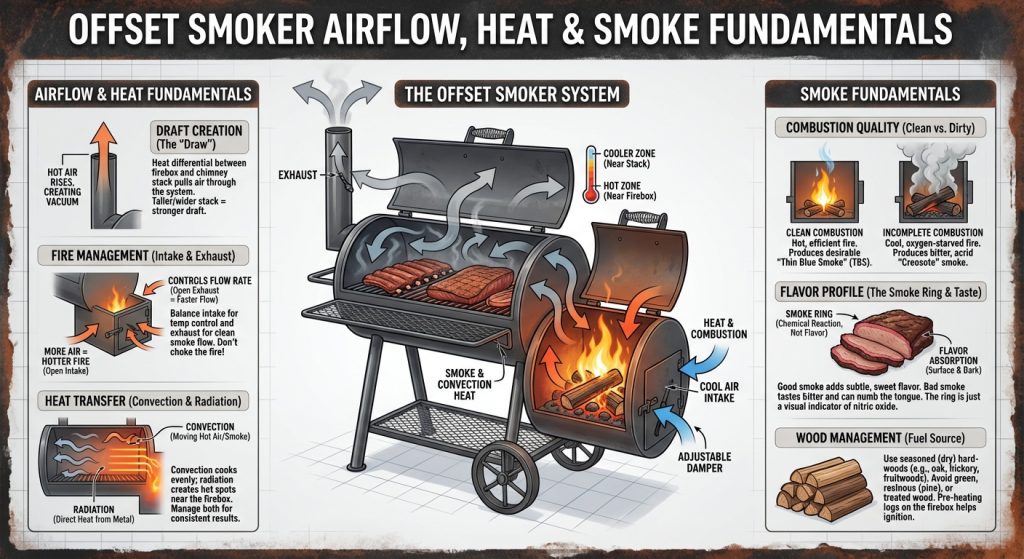

Offset smoker airflow fundamentals explain how heat and smoke move through an offset smoker and why airflow control matters for consistent cooking results.

An offset smoker is a horizontal, barrel-style cooker with a firebox attached to one side and a chimney on the opposite end. This layout separates the heat source from the cooking area, enabling true indirect smoking.

Understanding how smoke and heat move through an offset smoker turns barbecue from guesswork into controlled execution. Once you know why certain areas run hotter and others cooler, you can place meat intentionally, manage fire more efficiently, and achieve consistent results.

Heat and smoke movement in an offset smoker follows basic physics. Hot air rises and moves toward lower-pressure areas, carrying smoke particles with it. At the same time, the smoker’s metal construction conducts and radiates heat, creating the distinctive cooking environment inside the chamber.

Understanding airflow is a key part of choosing the right smoker, because heat movement, draft, and smoke circulation directly affect temperature stability and fuel efficiency.

Key Components of an Offset Smoker

To understand offset smoker heat and smoke flow, you must first understand its primary components.

The Firebox Chamber

The firebox is a smaller chamber attached to one end of the main barrel where wood splits or charcoal burn. It includes an adjustable air intake vent that controls oxygen supply to the fire.

The firebox connects to the cooking chamber through an opening, typically positioned low on the shared wall.

The Cooking Chamber

The cooking chamber is the main horizontal cylinder where food rests on one or more cooking grates. Most offset smokers position the cooking chamber floor slightly higher than the firebox floor, though designs vary.

The Chimney / Exhaust Stack

The chimney, or exhaust stack, allows smoke and combustion gases to exit the cooker. It usually includes an adjustable damper to control exhaust flow.

In traditional offset smokers, the chimney is located at the end of the cooking chamber opposite the firebox.

The Firebox-to-Cooking Chamber Passage

The opening between the firebox and cooking chamber is critical for efficient heat and smoke transfer. This passage is usually low on the cooking chamber side, allowing hot gases to enter naturally.

Its size and position strongly influence offset smoker heat distribution across the chamber.

How Heat Moves Through an Offset Smoker

Heat transfer occurs through three mechanisms: convection, conduction, and radiation.

Convection: The Primary Heat Transfer Method

Convection is the dominant form of offset smoker heat transfer. Hot air produced by the fire becomes less dense and rises, creating pressure that pushes it through the connecting passage into the cooking chamber.

Once inside, hot air continues flowing toward the chimney. Rising gases inside the chimney create negative pressure, pulling air through the system in a continuous draft.

The temperature difference between the firebox and outside air directly affects this convection current, which explains why offset smokers behave differently in summer versus winter conditions.

Conduction Heat Transfer

Heat conducts through the smoker’s metal structure. Firebox walls absorb heat from the fire and transfer it through the steel into the cooking chamber walls.

Cooking grates absorb heat from passing air and radiate it upward into the meat.

Thicker steel retains heat better and improves stability but requires more time and fuel to reach cooking temperature. Thinner steel heats faster but loses heat quickly, especially in cold or windy conditions. Smoker construction quality directly impacts both stability and efficiency.

Radiant Heat Effects

Radiant heat comes from several sources:

- Direct radiation from the firebox opening

- Heated cooking chamber walls emitting infrared energy

- Hot coals and burning wood inside the firebox

Radiant heat is strongest near the firebox side, creating the well-known hot spot, and gradually weakens toward the chimney end.

How Smoke Moves Through an Offset Smoker

Understanding smoke flow is just as important as understanding heat movement.

The Smoke Generation Process

Smoke forms during incomplete combustion of wood. Efficient combustion produces thin blue smoke, which is nearly invisible and rich in desirable flavor compounds.

Thick white smoke indicates poor combustion caused by insufficient heat or oxygen and results in bitter, acrid flavors.

Smoke quality is a direct reflection of fire management.

Smoke Flow Dynamics

Smoke particles travel with hot air through convection. As hot gases move from the firebox into the cooking chamber, smoke swirls around the food before exiting through the chimney.

Natural draft drives this movement. Rising hot gases in the chimney create lower pressure inside the cooking chamber, pulling smoke efficiently through the system.

Food placement and chamber obstructions influence turbulence, which can either improve smoke distribution or create dead zones.

The Role of the Chimney

The chimney is the engine that drives smoke movement. Taller chimneys generally create stronger draft, assuming sufficient internal temperature.

Chimney diameter affects flow volume, while placement determines the overall smoke path. Traditional offset smokers use horizontal flow from firebox to chimney, which ensures full exposure but creates temperature gradients.

Understanding offset smoker airflow fundamentals helps you diagnose hot spots and adjust firebox damper settings during long cooks.

Once you understand airflow fundamentals, design decisions like firebox size and baffle placement become much easier to evaluate.

Factors Affecting Smoke and Heat Distribution

Airflow Control

The intake damper controls oxygen supply. More air produces hotter, cleaner fires; too little air creates dirty smoke.

The exhaust damper controls how quickly smoke and heat leave the cooker. Strong draft increases airflow; restricted exhaust retains heat but risks smoke stagnation.

Balancing intake and exhaust is essential for stable offset smoker temperature control.

Temperature Gradients in the Cooking Chamber

Offset smokers naturally develop temperature differences:

- Firebox side is hottest

- Chimney side is coolest

- Top of chamber is warmer than bottom

Differences of 50–75°F across the chamber are common in unmodified smokers.

External Environmental Factors

Wind, ambient temperature, humidity, and precipitation all affect offset smoker airflow and performance. Wind can dramatically increase or disrupt draft, while cold weather increases heat loss through metal walls.

Experienced pitmasters adapt fire management to prevailing conditions.

Common Smoke and Heat Flow Problems

Poor Draft and Smoke Back-Up

Smoke backing into the firebox indicates draft problems, often caused by insufficient chimney height, blockages, or adverse wind conditions.

Uneven Heat Distribution

Hot spots near the firebox and cold spots near the chimney are normal but manageable. Side-to-side variations may result from airflow imbalance or chamber geometry.

Excessive Heat Loss

Common causes include:

- Poor door and lid seals

- Thin steel construction

- Leaks at the firebox-to-chamber connection

Many factory smokers benefit from gasket upgrades.

Optimizing Smoke and Heat Flow

Modifications to Improve Flow

Baffle plates and tuning plates redistribute heat by blocking direct radiant exposure and forcing lateral airflow.

Some setups create reverse flow, where gases travel under a plate before rising and flowing back toward the chimney.

Chimney extensions or repositioning can significantly improve draft and smoke flow.

Fire Management Techniques

Small, clean-burning fires are more efficient than large fires choked by dampers. Fire placement within the firebox affects radiant heat and temperature control.

Dry, seasoned hardwood produces cleaner smoke and steadier heat.

Cooking Chamber Setup

Water pans act as heat sinks, stabilize temperature swings, add humidity, and block direct radiant heat.

Strategic meat placement and occasional rotation compensate for natural gradients.

Measuring and Monitoring Flow Patterns

Temperature Monitoring Strategies

Built-in dome thermometers often read hotter than grate-level temperatures. Use multiple thermometers at grate level near the firebox, center, and chimney to map heat zones accurately.

Smoke Quality Assessment

Thin blue smoke indicates clean combustion. Thick white smoke signals airflow or fire problems.

Pleasant-smelling smoke equals good combustion; acrid smoke equals trouble.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is the firebox side always hotter?

Direct radiant heat and peak-temperature gas entry make the firebox side the hottest zone. This is normal in traditional offsets.

How does chimney position affect smoke flow?

Chimney placement determines smoke path. Traditional offsets use horizontal flow; reverse flow designs redirect gases beneath a baffle before exiting.

What is thin blue smoke?

Nearly invisible smoke from efficient combustion that delivers clean flavor without bitterness.

Can uneven heat be managed without modifications?

Yes—through fire size control, water pans, food placement, and rotation.

How do I know if draft is good?

Smooth smoke flow, stable temperatures, and thin blue smoke exiting the chimney indicate proper draft.

Does opening the cooking chamber door matter?

Yes. It disrupts pressure balance, drops temperature, and interrupts smoke flow for several minutes.

Key Takeaways

- Heat moves primarily by convection, with conduction and radiation contributing

- Smoke travels with hot air, driven by chimney-induced draft

- Intake and exhaust control both temperature and smoke quality

- Temperature gradients are normal and manageable

- Baffles improve distribution, but fire management matters most

- Environmental conditions significantly affect performance

Mastering how smoke and heat move through an offset smoker allows you to cook with intention, consistency, and efficiency—hallmarks of true pit mastery.